How Much Money Has Dixie Cups Made

Expansions of Liverpool boundaries in 1835, 1895, 1902, 1905 and 1913

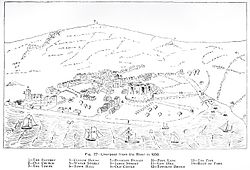

The history of Liverpool can be traced back to 1190 when the place was known as 'Liuerpul', possibly significant a puddle or creek with muddy water, though other origins of the name take been suggested. The borough was founded by royal charter in 1207 by Rex John, fabricated up of simply vii streets in the shape of the alphabetic character 'H'. Liverpool remained a small settlement until its trade with Ireland and coastal parts of England and Wales was overtaken by trade with Africa and the West Indies, which included the slave trade. The world's commencement commercial moisture dock was opened in 1715 and Liverpool's expansion to become a major city connected over the next two centuries.

By the outset of the nineteenth century, a large book of trade was passing through Liverpool. In 1830, the Liverpool and Manchester Railway was opened. The population grew quickly, especially with Irish migrants; by 1851, one quarter of the urban center'due south population was Irish-born. Equally growth connected, the city became known as "the 2nd metropolis of the Empire", and was also called "the New York of Europe". During the Second World State of war, the city was the centre for planning the crucial Boxing of the Atlantic, and suffered a rush 2d just to London's.

From the mid-twentieth century, Liverpool's docks and traditional manufacturing industries went into sharp decline, with the advent of containerisation making the city's docks obsolete. The unemployment charge per unit in Liverpool rose to one of the highest in the Great britain. Over the same menstruation, starting in the early 1960s, the city became internationally renowned for its civilisation, particularly as the centre of the "Merseybeat" sound which became synonymous with The Beatles. In contempo years, Liverpool's economy has recovered, partly due to tourism likewise as substantial investment in regeneration schemes. The city was the European Capital letter of Civilization for 2008.

Origins of the name [edit]

The name comes from the Old English liver, significant thick or muddy, and pol, meaning a puddle or creek, and is start recorded effectually 1190 as Liuerpul.[i] [two] Co-ordinate to the Cambridge Dictionary of English language Place-Names, "The original reference was to a puddle or tidal creek now filled up into which 2 streams drained".[two] The adjective Liverpudlian is first recorded in 1833.[2]

Early history of the area [edit]

The ancient neolithic Calder Stones on display in the Harthill Greenhouses

In the Fe Historic period the expanse around modern-mean solar day Liverpool was sparsely populated, though there was a seaport at Meols. The Calderstones are thought to be role of an ancient rock circle and there is archaeological evidence for native Fe Age farmsteads at several sites in Irby, Halewood and Lathom. The region was inhabited by Brythonic tribes, the Setantii likewise as nearby Cornovii and Deceangli. Information technology came nether Roman influence in about lxx AD, with the n advance to shell the druid resistance at Anglesey and to terminate the internal strife between the ruling family of Brigantes. The main Roman presence was at the fortress and settlement at Chester. According to Ptolemy, the Latin hydronym for the Mersey was Seteia Aestuarium, which derives from the Setantii tribe.[3] [4]

In 2007, evidence of a Roman tile works was institute effectually the Tarbock Isle area of the M62 and various Roman coins and jewellery accept been plant in the Liverpool area.[five]

After the withdrawal of Roman troops, land in the area connected to exist farmed by native Britons. The Hen Ogledd (Onetime North) was subject to fighting betwixt four medieval kingdoms: the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Mercia eventually defeated its rival Northumbria as well as the Celtic kingdoms of Gwynedd and Powys, with the Battle of Brunanburh possibly taking identify at nearby Bromborough. The settlements at Walton (Wealas tun meaning 'farmstead of the Wealas'), and Wallasey (Wealas-eg significant 'island of the Wealas') were named at this fourth dimension with Wealas being Old English language for 'foreigner' referring to the native Celtic and Romanized inhabitants.[6] [7]

The pseudo-historical Fragmentary Annals of Ireland appears to record the Norse settlement of the Wirral in its business relationship of the immigration of Ingimundr virtually Chester. This Irish gaelic source places this settlement in the aftermath of the Vikings' expulsion from Dublin in 902, and an unsuccessful effort to settle on Anglesey soon afterwards. Following these setbacks, Ingimundr is stated to have settled about Chester with the consent of Æthelflæd, co-ruler of Mercia.[8] The Norse settlers eventually joined upwards with another grouping of Viking settlers who populated west Lancashire, and for a time had an independent Viking mini-country, with Viking placenames evident all over Merseyside.

Origins of the town [edit]

W. Ferguson Irvine'southward conjectural plan of Liverpool'southward original 7 streets

Although a minor motte and bailey castle had earlier been congenital at Westward Derby, the origins of the city of Liverpool are usually dated from 28 August 1207, when letters patent were issued by Rex John advertising the establishment of a new borough, "Livpul", and inviting settlers to come and accept up holdings there. It is thought that the Male monarch wanted a port in the commune that was complimentary from the command of the Earl of Chester. Initially it served equally a dispatch bespeak for troops sent to Republic of ireland, before long subsequently the edifice around 1235 of Liverpool Castle, which was removed in 1726. St Nicholas Church was built by 1257, originally as a chapel within the parish of Walton-on-the-Hill.[nine] In the 13th Century, Liverpool as an area comprised merely vii streets.

With the formation of a marketplace on the site of the later Town Hall, Liverpool became established as a small fishing and farming community, administered past burgesses and, slightly later, a mayor. There was probably some littoral trade around the Irish gaelic Sea, and there were occasional ferries across the Mersey. However, for several centuries information technology remained a modest and relatively unimportant settlement, with a population of no more 1,000 in the mid 14th century. By the early fifteenth century a period of economic decline gear up in, and the county gentry increased their power over the town, the Stanley family unit fortifying their house by edifice Stanley Belfry on Water Street. This was a catalyst for a feud between the Stanley and Molyneux families since the Molyneux family had permission to live at the nearby Liverpool Castle at that time. The resulting rivalry about spilled into a riot in 1424.[10] In the heart of the 16th century the population of Liverpool had fallen to effectually 600, and the port was regarded every bit subordinate to Chester until the 1650s.

Elizabethan era and the Civil War [edit]

In 1571 the people of Liverpool sent a memorial to Queen Elizabeth, praying relief from a subsidy which they thought themselves unable to bear, wherein they styled themselves "her majesty's poor decayed town of Liverpool." Some fourth dimension towards the shut of this reign, Henry Stanley, 4th Earl of Derby, on his way to the Isle of Man, stayed at his house, the Tower; at which the corporation erected a handsome hall or seat for him in the church, where he honoured them several times with his presence.

By the stop of the sixteenth century, the town began to be able to have advantage of economic revival and the silting of the River Dee to win merchandise, mainly from Chester, to Republic of ireland, the Mann and elsewhere. In 1626, King Charles I gave the town a new and improved charter.[ix]

In June 1644 Prince Rupert of the Rhine arrived in Liverpool with x,000 men in an endeavor to capture Liverpool Castle. A sixteen-day siege of Liverpool and then took place.[11] To defend the city the Parliament Army created a huge trench across much of the boondocks heart. Prince Rupert eventually took hold of the Castle only to be driven out once again to take refuge in the Everton area of the city, hence the name of the belfry institute on the modern twenty-four hours Everton Football game Social club badge is known equally Prince Rupert's Belfry.

Transatlantic merchandise [edit]

The first cargo from the Americas was recorded in 1648. The development of the town accelerated afterwards the Restoration of 1660, with the growth of trade with America and the Due west Indies. From that time may be traced the rapid progress of population and commerce, until Liverpool had become the second city of Great United kingdom. Initially, cloth, coal and common salt from Lancashire and Cheshire were exchanged for saccharide and tobacco; the boondocks's first sugar refinery was established in 1667.[12]

In 1699 Liverpool was made a parish on its ain by Act of Parliament, separate from that of Walton-on-the-Hill, with 2 parish churches. At the same fourth dimension it gained separate community dominance from Chester.[nine]

Slave trade, privateering [edit]

In 1699 the offset known slave ship to sail from Liverpool departed, its name and number of victims unknown.[13] The concluding recorded slaving voyage out of Liverpool was in 1862, of a total of 4,973 such voyages.[13] I example is the Liverpool Merchant that set sail for Africa on 3 Oct 1699, the very same year that Liverpool had been granted status as an contained parish. Information technology arrived in Barbados with a 'cargo' of 220 Africans, returning to Liverpool on eighteen September 1700. Past the close of the 18th century xl% of the world'south, and 80% of Britain'due south activeness in the Atlantic slave trade was deemed for by slave ships that voyaged from the docks at Liverpool. In the elevation year of 1799, ships sailing from Liverpool carried over 45,000 enslaved people from Africa.[9]

Liverpool merchants such as Foster Cunliffe and his apprentice William Bulkeley co-owned voyages for slaves, for Greenland whaling, and, peculiarly during the 7 Years' War, privateering.[14] They traded also in tobacco and other commodities.[15] James Stonehouse recalled his father's ship existence fitted out: "I was oftentimes taken on board. In her hold were long shelves, with ring bolts in rows in several places. I used to run along these shelves little thinking of what dreadful scenes would be enacted upon them. The fact is that [she] was destined for the African trade, in which she made many successful voyages. In 1779, however, she was converted into a privateer. My father, at the present time, would non possibly be thought very respectable; but I clinch you that he was so considered in those days. So many people in Liverpool were... "tarred with the same brush" that these occupations were... not at all regarded as derogatory."

Vast profits transformed Liverpool into ane of United kingdom'due south foremost cities. Liverpool became a fiscal centre, rivaled by Bristol, another slaving port, and exceeded only by London. The first commercial wet dock in the world was congenital in Liverpool and completed in 1715, with a capacity of 100 ships. The commercial growth led to the opening of the Consulate of the United States in Liverpool in 1790, its first consulate anywhere in the world, and to many other social changes: "As a young boy, I have seen it ranked only equally a third-class seaport. Its streets tortuous and narrow, with pavements in the center, skirted by mud or clay as the season happened. The sidewalks rough with sharp-pointed stones, that made it misery to walk upon them. I have seen houses, with little low rooms, suffice for the home of the merchant or well-to-do trader, the first being content to live in H2o-St. or Oldhall-St., while the latter had no idea of leaving his piffling store, with its bay or foursquare window, to accept intendance of itself at night... The well-nigh enlightened of its inhabitants, at that time, could not boast of much intelligence, while [the] lower orders were plunged in the deepest vice, ignorance, and brutality... so barbarous were they in their amusements, bullbaiting and erect and dog fightings, and pugilistic encounters. What could we expect when we opened no book to the young... deriving our prosperity from two great sources - the slave trade and privateering... Swarming with sailormen flushed with prize money, was it non likely that the inhabitants generally would take a tone from what they daily beheld and quietly countenanced?...

Equally a human, I take seen the sometime narrow streets widening - the old houses aging... and the body of water influence recede before improvement, education and enlightenment of all sorts. The three-canteen and dial drinking human being is the exception at present, and non the rule of the table." [16]

Liverpool politicians and slavery [edit]

Richard Pennant was returned unopposed as one of the two Members of Parliament for Liverpool at a by-election in 1767. He and then won two successive general elections, in 1768 and 1774. He was defeated in 1780 full general election, when Bamber Gascoyne (the younger) was returned instead. Pennant was given an Irish peerage, becoming Lord Penrhyn.[17] He was returned as an MP for Liverpool in the 1784 general ballot. Between 1784 and 1790, when he stood down and was replaced past Banastre Tarleton, Penrhyn is reported to take made more than than 30 speeches, all in vigorous defence of Liverpool merchandise or the W Indies. From 1788 to 1807, he was also Chairman of the London Society of West India Planters and Merchants.[xviii] In May 1788, Penrhyn and Bamber Gascoyne (the younger), were the only two Members who ventured to justify the slave merchandise. Penrhyn spoke frequently in defence of the slave trade 'denying the facts advanced, highly-seasoned to the prudence and policy of the House against their compassion'. On 12 May 1789 he told the Firm that 'if they passed the vote of abolitionism they actually struck at lxx millions of belongings, they ruined the colonies, and past destroying an essential nursery of seamen, gave up the dominion of the sea at a unmarried glance'. Bamber Gascoyne continued as a Liverpool MP until 1796.[17]

Banastre Tarleton succeeded Lord Penrhyn every bit MP in 1790, and apart from one twelvemonth, remained as an MP for Liverpool until 1812. He was a frequent speaker in the Business firm of Commons, 'spirited and animated', in debate. In 1791 he visited Paris and was barred from the Jacobin Club because of his consequent and outspoken defence of the slave trade. His rhetoric was versatile; in 1794 he opposed William Wilberforce'due south bid to veto the export of slaves to foreign countries as an attack on individual belongings. In 1796 he thwarted a further bid to abolish the slave merchandise and went on to thwart the slave carrying beak. In 1803 his opposition to abolition of the slave merchandise was based on the danger from Napoleon, calculation in 1805 that Liverpool's growth and prosperity depended on the trade. By 1806 he believed that the U.s.a. would do good more from abolition, and he 'was sorry to discover that ministers were much more active in injuring the trade of the country than in providing for its defense force'.[19]

Fifty-fifty in Liverpool, abolitionist sentiment was expressed. The Liverpool-born pol William Roscoe was member for Liverpool in 1806–1807, and was able to vote for the abolition of the slave trade in 1807.[20] This legislation imposed fines that did little to deter slave merchandise participants; 29 avowed slaving voyages left Liverpool in 1808, but none in 1809, 2 in 1810, and two more in 1811. In 1811 Henry Brougham introduced the Slave Merchandise Felony Act 1811 which made slave traders liable to constructive penalties including penal transportation for upward to fourteen years.[21] Thereafter, though the trade connected in illicit forms, only one more slaving voyage, in 1862, is recorded from Liverpool.[13] Many merchants managed to ignore the laws and continued to deal in slave trafficking, supplying the markets that remained open in Brazil and elsewhere.

Slavery in British colonies was finally abolished in 1833, replaced by "apprenticeships", which ran until 1838 when they were abolished too.[22]

Industrial revolution and commercial expansion [edit]

-

-

-

Colourised photo taken in the 1890s. (note the partial view of the lost tympanum)

The international merchandise of the metropolis grew, based, as well as on slaves, on a wide range of commodities - including, in particular, cotton, for which the city became the leading earth market, supplying the textile mills of Manchester and Lancashire.

During the eighteenth century the town's population grew from some half-dozen,000 to eighty,000, and its land and water communications with its hinterland and other northern cities steadily improved. Liverpool was first linked past canal to Manchester in 1721, the St. Helens coalfield in 1755, and Leeds in 1816. In 1830, Liverpool became home to the earth'southward first inter-urban rail link to another city, Manchester, through the Liverpool and Manchester Railway and the maiden journey Stephenson'south The Rocket railroad train.[23]

Liverpool's importance was such that it was home to a number of earth firsts, including gaining the world's first fully electrically powered overhead railway, the Liverpool Overhead Railway, which was opened in 1893 and so pre-dated those in both New York City and Chicago.

The built-up expanse grew rapidly from the eighteenth century on. The Bluecoat Hospital for poor children opened in 1718. With the demolition of the castle in 1726, only St Nicholas Church and the celebrated street programme - with Castle Street equally the spine of the original settlement, and Paradise Street following the line of the Pool - remained to reflect the town's mediaeval origins. The Town Hall, with a covered exchange for merchants designed by builder John Wood, was built in 1754, and the first office buildings including the Corn Substitution were opened in about 1810.

Throughout the 19th century Liverpool's trade and its population continued to expanded rapidly. Growth in the cotton trade was accompanied past the development of strong trading links with Republic of india and the Far East post-obit the ending of the Honourable East India Visitor's monopoly in 1813. Over 140 acres (0.57 kmii) of new docks, with 10 miles (sixteen km) of quay space, were opened between 1824 and 1858.[9] In 1848 Liverpool'south public abattoir in the city centre was considered the all-time in England, though by 1900 information technology was said to be in some respects inferior to a private abattoir.[24]

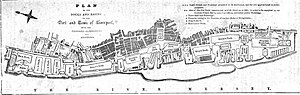

Map of Liverpool from 1880

During the 1840s, Irish migrants began arriving by the thousands due to the Slap-up Famine of 1845–1849. Almost 300,000 arrived in the year 1847 alone, and past 1851 approximately 25% of the city was Irish-built-in. The Irish influence is reflected in the unique place Liverpool occupies in Uk and Irish political history, being the simply place outside Ireland to elect a member of parliament from the Irish Parliamentary Party to the British parliament in Westminster. T.P. O'Connor represented the constituency of Liverpool Scotland from 1885 to 1929.

As the town became a leading port of the British Empire, a number of major buildings were constructed, including St. George's Hall (1854), and Lime Street Station. The Grand National steeplechase was first run at Aintree in 1837.[25]

Between 1851 and 1911, Liverpool attracted at least twenty,000 people from Wales in each decade, peaking in the 1880s, and Welsh civilisation flourished. One of the outset Welsh language journals, Yr Amserau, was founded in Liverpool by William Rees (Gwilym Hiraethog), and there were over 50 Welsh chapels in the city.[26]

Early regular scheduled Liverpool transatlantic passenger travel began in the 1810s with American lines such every bit Black Ball Line (trans-Atlantic packet) and Collins Line and in the 1840s with Liverpool-based companies' lines Cunard Line and White Star Line standing throughout the 19th Century.

When the American Ceremonious State of war bankrupt out Liverpool became a hotbed of intrigue. Given the crucial place cotton held in the metropolis's economic system, during the American Ceremonious War Liverpool was, in the words of the historian Sven Beckert, "the most pro-Confederate identify in the globe outside the Confederacy itself."[27] The Confederate Navy send, the CSS Alabama, was congenital at Birkenhead on the Mersey and the CSS Shenandoah surrendered there (existence the final surrender and end of the war).[ citation needed ]

Liverpool was granted urban center status in 1880, and the following year its university was established. By 1901, the city'south population had grown to over 700,000, and its boundaries had expanded to include Kirkdale, Everton,[28] Walton, West Derby (in 1835 and 1895), Toxteth and Garston.[9]

20th century [edit]

1900-1938 [edit]

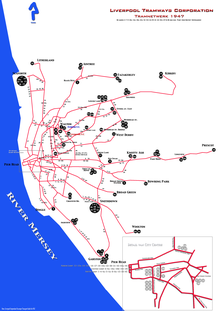

By 1957, the once-great Liverpool tramway arrangement had been reduced to merely two routes, the 6A to Bowring Park and the twoscore to Folio Moss Avenue. These routes finally closed in September. All were in a run-downwardly and dilapidated condition, sad to see. Here is a 'Baby One thousand' 4-wheel tram on the Bowring Park route.

Liverpool Corporation Tramway Routes in 1947

Queens Bulldoze, Walton, Liverpool, pictured in 1909

During the beginning function of the 20th century Liverpool continued to aggrandize, pulling in immigrants from Europe. In 1903 an International Exhibition took place in Edge Lane. In 1904, the building of the Anglican Cathedral began, and by 1916 the iii Pier Head buildings, including the Liver Building, were consummate. This menstruation marked the peak of Liverpool's economical success, when it regarded itself as the "2nd urban center" of the British Empire.[nine] The formerly independent urban districts of Allerton, Childwall, Piddling Woolton and Much Woolton were added in 1913, and the parish of Speke added in 1932, with large housing developments, generally past the local authorization, being built over the next few years.[29]

Adolf Hitler's half-brother Alois and his Irish gaelic sis-in-constabulary Bridget Dowling are known to take lived in Upper Stanhope Street in the 1910s. Bridget's alleged memoirs, which surfaced in the 1970s, said that Adolf stayed with them in 1912–13, although this is much disputed as many believe the memoirs to be a forgery.[30] [31] [32]

The maiden voyage of Titanic in Apr 1912 was originally planned to depart from Liverpool, as Liverpool was its port of registration and the dwelling house of owners White Star Line. Yet, it was changed to depart from Southampton instead.

Aside from the large Irish customs in Liverpool, there were other pockets of cultural diverseness. The area of Gerard, Hunter, Lionel and Whale streets, off Scotland Road, was referred to as Picayune Italy. Inspired by an quondam Venetian custom, Liverpool was 'married to the sea' in September 1928. Liverpool was also home to a large Welsh population, and was sometimes referred to every bit the Upper-case letter of North Wales. In 1884, 1900 and 1929, Eisteddfods were held in Liverpool.

Economic changes began in the outset part of the 20th century, equally falls in world demand for the N West'southward traditional consign commodities contributed to stagnation and decline in the city. Unemployment was well to a higher place the national average equally early as the 1920s, and the city became known nationally for its occasionally violent religious sectarianism.[9]

When Everton F.C. won the Football League Starting time Division championship in 1928, their center-forrad Dixie Dean scored a Football game League record of 60 goals in the aforementioned season.

The Smashing Depression hit Liverpool badly in the early 1930s with thousands of people in the city left unemployed. This was combated by a large amount of housing mostly congenital by the local quango being constructed, creating jobs mostly in the building, plumbing and electrical trades. Most 15 per cent of the city's population were rehoused in the 1920s and 1930s with more 30,000 new council houses beingness built to replace the slums in the metropolis.

The ascension popularity of motor cars led to congestion in the urban center, and in 1934 the city gained its first direct road link with the Wirral Peninsula, when the beginning Mersey Tunnel road was opened. The Queensway, as the new tunnel was named, linked Liverpool with Birkenhead at the other side of the Mersey. Many other buildings were built in the city in the 1930s to ease the depression and became local landmarks, with many buildings featuring American inspired architecture.[33]

1939-1945: Globe State of war II [edit]

During World War 2, Liverpool was the control eye for the Boxing of the Atlantic. There were eighty air-raids on Merseyside, with an especially full-bodied series of raids in May 1941 which interrupted operations at the docks for about a week. Some 2,500 people were killed,[34] most half the homes in the metropolitan area sustained some impairment and some eleven,000 were totally destroyed. Over 70,000 people were made homeless.[9] John Lennon, one of the founding members of The Beatles, was born in Liverpool during an air-raid on ix October 1940. All four members of The Beatles were built-in in the city during the war, rising to fame in the early 1960s.

Thousands of Chinese sailors were recruited to aid the war effort and came to Liverpool, many forming relationships with local women. However, one time the war was concluded, they were mostly forcibly repatriated.[35] [36]

1946-1979 [edit]

Significant rebuilding followed the war, including massive housing estates and the Seaforth Dock, the largest dock project in United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland. Yet, the city has been suffering since the 1950s with the loss of numerous employers. Past 1985 the population had fallen to 460,000. Declines in manufacturing and dock activity struck the urban center particularly difficult. In 1956 Liverpool Overhead Railway and its fourteen stations were closed and demolished and in 1957 Liverpool Corporation Tramways closed after the last tram ran in Liverpool.

In 1955, the Labour Party, led locally by Jack and Bessie Braddock, came to ability in the City Quango for the commencement time.

In 1956, a private pecker sponsored by Liverpool City Council was brought earlier Parliament to develop a h2o reservoir from the Tryweryn Valley. The development would include the flooding of Capel Celyn. By obtaining authority via an Act of Parliament, Liverpool City Council would not require planning consent from the relevant Welsh local authorities.

In the 1960s Liverpool became a heart of youth civilisation. The city produced the distinctive Merseybeat sound, most famously The Beatles, and the Liverpool poets.

From the 1970s onwards Liverpool's docks and traditional manufacturing industries went into farther abrupt decline. The advent of containerisation meant that Liverpool's docks ceased to be a major local employer. Liverpool Central High Level railway station closed in 1972, equally well equally the Waterloo, Victoria and Wapping tunnels. In 1974, Liverpool became a metropolitan district within the newly created metropolitan county of Merseyside. In 1977 Liverpool Exchange railway station closed, and in 1979 the North Liverpool Extension Line closed also. In 1972 Canadian Pacific unit CP Ships were the last transatlantic line to operate from Liverpool.

1980s [edit]

The 1980s saw Liverpool's fortunes sink to their lowest postwar betoken. Although the 1970s, along with the residuum of Britain, had brought economical difficulties and a steady rise in unemployment, the situation in Liverpool went from bad to worse in the early 1980s, with endless factory closures and some of the highest unemployment rates in the United kingdom. An average of 12,000 people each yr were leaving the urban center, and fifteen% of its state was vacant or derelict.[ix]

In July 1981 the infamous Toxteth Riots took place, during which, for the first fourth dimension in the UK outside Northern Republic of ireland, tear gas was used by police against civilians. In the same yr, the Tate and Lyle sugar works, previously a mainstay of the urban center's manufacturing economy, closed down. The docks had already declined dramatically by this stage, depriving the metropolis of another major source of employment.

By 1985, unemployment in Liverpool exceeded xx%, around double the national average. Nigh this fourth dimension the scourge of heroin, always present in port cities, began to rising.

Liverpool Urban center Council was dominated past the far-left wing Militant group during the 1980s, under the de facto leadership of Derek Hatton (although Hatton was formally only Deputy Leader). The metropolis council sank heavily into debt, as the City Council fought a campaign to forestall central government from reducing funding for local services. Ultimately this led to 49 of the city'southward Councillors beingness removed from office by the District Auditor for refusing to cut the budget, refusing to make skilful the deficit and forcing the Urban center Council into virtual bankruptcy. The conduct of Hatton and the militant tendency had fifty-fifty come up under the scrutiny of Labour Party leader Neil Kinnock, who was swell to remove the militant tendency from the party as role of the endeavour to make information technology electable once more. At the same time, the Conservative authorities of Margaret Thatcher was deeply unpopular in Liverpool, with the Conservatives share of the vote in most local council and parliamentary elections being consistently low throughout the 1980s.

On 15 April 1989, 97 Liverpool F.C. fans (by and large from Merseyside also as neighbouring parts of Cheshire and Lancashire) died in the Hillsborough disaster at an FA Cup semi-last in Sheffield. This had a traumatic effect on people across the land, particularly in and around the city of Liverpool, and resulted in legally imposed changes in the fashion in which football fans have since been accommodated, including compulsory all-seater stadiums at all leading English clubs by the mid-1990s. Many clubs removed their perimeter fencing almost immediately subsequently the tragedy, and such measures at football grounds in England have long since been banned.

In particular this led to stiff feeling in Liverpool because information technology was widely reported in the media that the Liverpool fans were at fault. The Sun sparked detail controversy for publishing these allegations in an article four days later the disaster. Sales of the newspaper in Liverpool slumped and many newsagents refused to stock it. Three decades later, many people in the city still refuse to buy The Dominicus and a number of newsagents still pass up to sell information technology. Other media outlets including the Daily Star and Daily Postal service besides printed similar stories in which the behaviour of Liverpool fans was alleged to have been a major gene in the tragedy.

There was further controversy surrounding the tragedy in March 1991 when a verdict of accidental expiry was recorded on the 95 people who had died at Hillsborough (the 96th victim did non die until 1993), much to the dismay of the bereaved families, who had been hoping for a verdict of unlawful killing, or an open verdict, to be recorded; and for criminal charges to be brought confronting Due south Yorkshire Police. This verdict was somewhen replaced by one of unlawful killing at fresh inquest 25 years later.

It has since become clear that South Yorkshire Police fabricated a range of mistakes at the game, though the senior officer in charge of the upshot retired soon later.

The success of Liverpool FC was some compensation for the metropolis's economical misfortune during the 1970s and 1980s. The society, formed in 1892, had won five league titles by 1947, only enjoyed its showtime consequent run of success under the direction of Bill Shankly between 1959 and 1974, winning a further iii league titles as well as the club's first two FA Cups and its showtime European bays in the shape of the UEFA Cup. Following Shankly'due south retirement, the society continued to dominate English football for nearly xx years after. By 1990, Liverpool FC had won more major trophies than any other English social club - a total of xviii summit division league titles, four FA Cups, four Football League Cups, four European Cups and ii UEFA Cups.[37] The social club's iconic red shirt had been worn by some of the biggest names in British sport of the 1970s and 1980s, including Kevin Keegan, Kenny Dalglish (who as well served as manager from 1985 to 1991 and once more from 2011 to 2012), Phil Neal, Ian Rush, Ian Callaghan and John Barnes. The guild has since won their beginning Premier League title and a farther 3 FA Cups, 3 League Cups, a UEFA Cup and 2 European Cups, and fielded a new wave of stars including Robbie Fowler, Michael Owen, Jamie Carragher and Steven Gerrard.[38]

Everton F.C., the city'southward original senior football society, also enjoyed a degree of success during the 1970s and 1980s. The society had enjoyed a consistent run of success during the interwar years and again in the 1960s, just after winning the league title in 1970 went 14 years without winning a major trophy, although they did hold onto the Kickoff Division place which had been theirs since 1954. Then, in 1984, Everton won the FA Loving cup under the management of Howard Kendall, who had once been a player at the club.[39] A league title win followed in 1985, forth with the club's first European trophy - the European Cup Winners' Loving cup.[xl] By 1986, the city's two clubs were firmly established as the leading club sides in England as Liverpool finished league champions and Everton runners-upwardly, and the two sides also met for the FA Cup final, which Liverpool won 3–1. The Everton side of the mid-1980s included some of the highest rated footballers in the English league at the time; goalkeeper Neville Southall, winger Trevor Steven, forwards Graeme Abrupt and Andy Grey, and Gray'south successor Gary Lineker.

Everton have enjoyed an unbroken run in the top flying of English football since 1954, although their merely major bays since the league title in 1987 came in 1995 when they won the FA Loving cup.[41] Everton added some other league title in 1987, with Liverpool finishing runners-upward.[42]

Another all-Merseyside FA Cup final 1989 saw Liverpool beat Everton 3–2. This match was played just five weeks after the Hillsborough disaster.[43]

1990s [edit]

A similar national outpouring of grief and stupor to the Hillsborough disaster occurred in February 1993 when James Bulger was killed by two 10-year-old boys, Jon Venables and Robert Thompson. The two boys were found guilty of murder later in the year and sentenced to indefinite detention.

The 1990s saw the continued regeneration of the metropolis which had started in the 1980s. This is still happening in 2020.

Recent history [edit]

A general economic and borough revival has been underway since the mid-nineties. Liverpool'southward economy has grown faster than the national average and its criminal offence levels have remained lower than most other metropolitan areas in England and Wales, with recorded crime per head in Merseyside comparable to the national average — unusually low for an urban area.

In recent years, the urban center has emphasised its cultural attractions. Tourism has go a significant cistron in Liverpool'due south economy, capitalising on the popularity of The Beatles and other groups of the Merseybeat era. In June 2003, Liverpool won the correct to be named European Capital of Culture for 2008, beating other British cities such equally Newcastle and Birmingham to the coveted title. The riverfront of the urban center was also designated as a Earth Heritage Site in 2004 until its revocation in 2021.

In October 2005, Liverpool Metropolis Council passed a public apology for the flooding of Capel Celyn in Wales.[ citation needed ]

In October 2007, Liverpool and London continued with wildcat strikes, after the stop of the official CWU strikes, that had been ongoing since June in a dispute with the Royal Post over pay, pensions, and hours.

On Nov 11, 2021, a flop inside a taxi detonated outside Liverpool Women's Infirmary. It has been recognised as a terror assault.

Run into also [edit]

- History of housing in Liverpool

- Timeline of Liverpool

References [edit]

- ^ Hanks, Patrick; Hodges, Flavia; Mills, David; Room, Adrian (2002). The Oxford Names Companion. Oxford: the Academy Press. p. 1110. ISBN0198605617.

- ^ a b c Harper, Douglas. "Liverpool". The Online Etymology Lexicon.

- ^ "Our ancestors and the Roman invasion". Museum of Liverpool . Retrieved 2 Apr 2014.

- ^ "Celtic kingdoms of the British Isles". The History Files . Retrieved iii April 2014.

- ^ "Roman Liverpool". History of Liverpool . Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ Ekwall, Eilert (1936). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-names. OUP.

- ^ "Wales". The Complimentary Dictionary . Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Downham, C (2007). Viking Kings of Britain and Republic of ireland: The Dynasty of Ívarr to A.D. 1014. Edinburgh: Dunedin Bookish Press. pp. 27–28, 83–84, 206–209, 256. ISBN978-1-903765-89-0.

- ^ a b c d e f thou h i j Belchem, John, ed. (2006). Liverpool 800: Civilisation, Character & History. ISBNi-84631-035-0.

- ^ "Text only version of our interactive Liverpool Molyneux Stanley family history page". The History of Liverpool . Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ "Civil State of war Siege of Liverpool". The History of Liverpool.

- ^ "loc-liverpool". Mawer.clara.net . Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ a b c "Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade - Database". Slavevoyages.org . Retrieved 16 Apr 2021.

- ^ History of the Liverpool Privateers and Letters of Marque, with an account of the Liverpool Slave Merchandise, 1744-1812. pp. 80-83. Gomer Williams. Reprint of the 1897 edition (William Heinemann (London) and Edward Howell (Liverpool), McGill University, Canada, 2004 ISBN 0-7735-2746-10

- ^ Walsh, Lorena S. (i December 2012). Motives of Honour, Pleasure, and Profit: Plantation Management in the Colonial Chesapeake, 1607-1763. UNC Press Books. ISBN9780807895924 – via Google Books.

- ^ Recollections of a Nonagenarian, by the late Mr James Stonehouse. Equally quoted in History of the Liverpool Privateers and Letters of Marque, with an account of the Liverpool Slave Trade, 1744-1812. pp. 187-189. Gomer Williams. Reprint of the 1897 edition (William Heinemann (London) and Edward Howell (Liverpool), McGill University, Canada, 2004 ISBN 0-7735-2746-X

- ^ a b "PENNANT, Richard (?1736–1808), of Penrhyn Hall, Carnarvon, and Winnington, Cheshire". History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ David Beck Ryden (March 2012). "Sugar, spirits, and forage: The London West Bharat involvement and the glut of 1807". Atlantic Studies. 9: 41–64. doi:10.1080/14788810.2012.636995. S2CID 218622730. Retrieved five December 2020.

- ^ "TARLETON, Banastre (1754-1833), of St. James's Identify, Mdx. Published in The History of Parliament: the House of Eatables 1790-1820, ed. R. Thorne, 1986". Historyofparliamentonline.org . Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ "Liverpool Slave Trade". History of Liverpool. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ^ "THE TRIALS OF THE SLAVE TRADERS SAMUEL SAMO, JOSEPH PETERS, AND WILLIAM TUFFT, TRIED IN APRIL AND JUNE, 1812, Earlier THE HON. ROBERT THORPE, L.L.D. Chief Justice of Sierra Leone, &c. &c. WITH TWO Letters ON THE SLAVE Merchandise, FROM A GENTLEMAN RESIDENT AT SIERRA LEONE TO AN Abet FOR THE Abolitionism, IN LONDON. LONDON: PRINTED FOR SHERWOOD, NEELEY AND JONES, PATERNOSTER-ROW; AND TO Exist HAD OF ALL OTHER BOOKSELLERS 1813". En.wikisource. p. 30.

- ^ "Liverpool Local History - American Connections - Slavery Timeline". BBC . Retrieved 25 Nov 2015.

- ^ "KS3 History Railways". The History of Liverpool . Retrieved 25 Nov 2015.

- ^ Otter, Chris (2020). Diet for a big planet. USA: Academy of Chicago Printing. p. 38. ISBN978-0-226-69710-nine.

- ^ "KS3 History Victorian Times". History of Liverpool.

- ^ Davies, John (1993). A History of Wales. ISBN0-fourteen-028475-three.

- ^ Beckert, Sven (2014). Empire of Cotton fiber: a Global History. New York: Knopf.

- ^ O'Connor, Freddy (1990). Liverpool: Our City, Our Heritage. ISBN0-9516188-0-6.

- ^ "Liverpool CB/MB". A vision of Britain through time. Archived from the original on 31 August 2012.

- ^ Royden, Chiliad.W. "Adolf Hitler - did he visit Liverpool during 1912-thirteen?". Mike Royden'southward Local History Pages. Archived from the original on nineteen July 2012.

- ^ Royden, M West. "Legacies - Your Story: Adolf Hitler - did he visit Liverpool during 1912-13?". BBC Online . Retrieved 25 Nov 2015.

- ^ "Hitler in Liverpool". The History of Liverpool . Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Coslett, Paul. "Creativity in the Great Depression". BBC. Archived from the original on 27 June 2013.

- ^ Some sources state 4,000

- ^ "Looking for my Shanghai father". Bbc.co.united kingdom of great britain and northern ireland. 24 Baronial 2015. Retrieved xvi Apr 2021.

- ^ "Heart-breaking hidden story of Liverpool Chinese families revealed in new exhibition". Edgehillac.uk. 5 February 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ "Liverpool FC Honours Listing". This is Anfield . Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ "Liverpool Legends". Pinterest . Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ "1981 - 2002". Everton F.C. Archived from the original on thirty January 2013.

- ^ "1981 - 2002". Everton F.C. Archived from the original on 24 January 2012.

- ^ "1981 - 2002". Everton F.C. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012.

- ^ "1986/87 Season". Everton F.C. Archived from the original on 18 June 2013.

- ^ "FA Cup final memories: 1989". Liverpool FC. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014.

Further reading [edit]

- Belchem, John (2007). Irish, Cosmic and Scouse: The History of the Liverpool-Irish, 1800-1939. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

External links [edit]

- The History of Liverpool

- Various tales from Liverpool's history

- Liverpool Slavery Remembrance Initiative

- British History Online

- Liverpool John Moores University

- BBC Local History

- Local Histories

- Liverpool and the American Civil State of war

- "Liverpool and the Slave Trade", lecture by Anthony Tibbles at Gresham College, 19 March 2007 (available for download as video or audio files)

- Liverpool The Gateway To America

- Recollections of Onetime Liverpool, by A Nonagenarian, published 1836, from Projection Gutenberg

- Ward Lock Guide to Liverpool, excerpts, published 1949

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Liverpool

Posted by: royfationsuld45.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Much Money Has Dixie Cups Made"

Post a Comment